FROM A MAZE TO A(MAZE)D

Huasipichanga participated from the Child-responsive urban planning workshop organized by ISOCARP, UNICEF and the China Urban Planning Society on August 2019. With a team of locals and internationals, a proposal was developed to transform the spaces in the Mingdong Community into child-responsive spaces re-imagined by children themselves.

THE PLACE

Young Planning Professionals Workshop in Ningbo China

Child-responsive urban planning represents a new approach to develop urbanism at a human scale. From August 26th to 30th August 2019 ISOCARP, UNICEF, the China Urban Planning Society (UPSC), Ningbo Bureau of Nature Resources and Planning (NBNRP), the Ningbo Urban Planning & Design Institute (NBPI) and the ISOCARP Institute, Centre for Urban Excellence organized a workshop on child-responsive urban planning to be held in Ningbo-China, awarded “China’s most Happy City” nine times.

Huasipichanga was selected as a participant to join one of the working groups that would develop a proposal to transform the case study area: the Mingdong community. With a team of four locals and two internationals, developed the proposal “From a maze to a(maze)d” that aims to transform Mindong from a space where children feel trapped and bored into a place where they find surprises everywhere, where they can move around freely while learning and having fun, a place to be a(maze)d.

METHODOLOGY

SCREENING

As a team we defined certain tasks to be performed during the process. First, the need to feel the place, understand it with our senses, walk around, see, smell, feel and experience the place as a group and individually. Secondly, it was necessary to talk with the inhabitants, listen to their needs but also listen to the activities they like to do and the elements that they enjoy about the place they live in, to enhance this feeling with our proposal. Children were the center of this discussions and dialogues. Next, with the data collected and with the literature on our hands we would propose some first ideas as a team, but also let the children propose their own ideas. This is a way to validate our expertise taking into account that the people in the community are also experts, they know very well the dynamics of the place. Our aim is to broaden the spectrum of possibilities for the place, but always making sure that whatever is created matches with what the children of Mindong imagine for their community. Finally, we came up with a holistic proposal which was entirely developed with the children and has envisions Mindong as a national and international example of child-friendly neighborhoods.

PICTURING

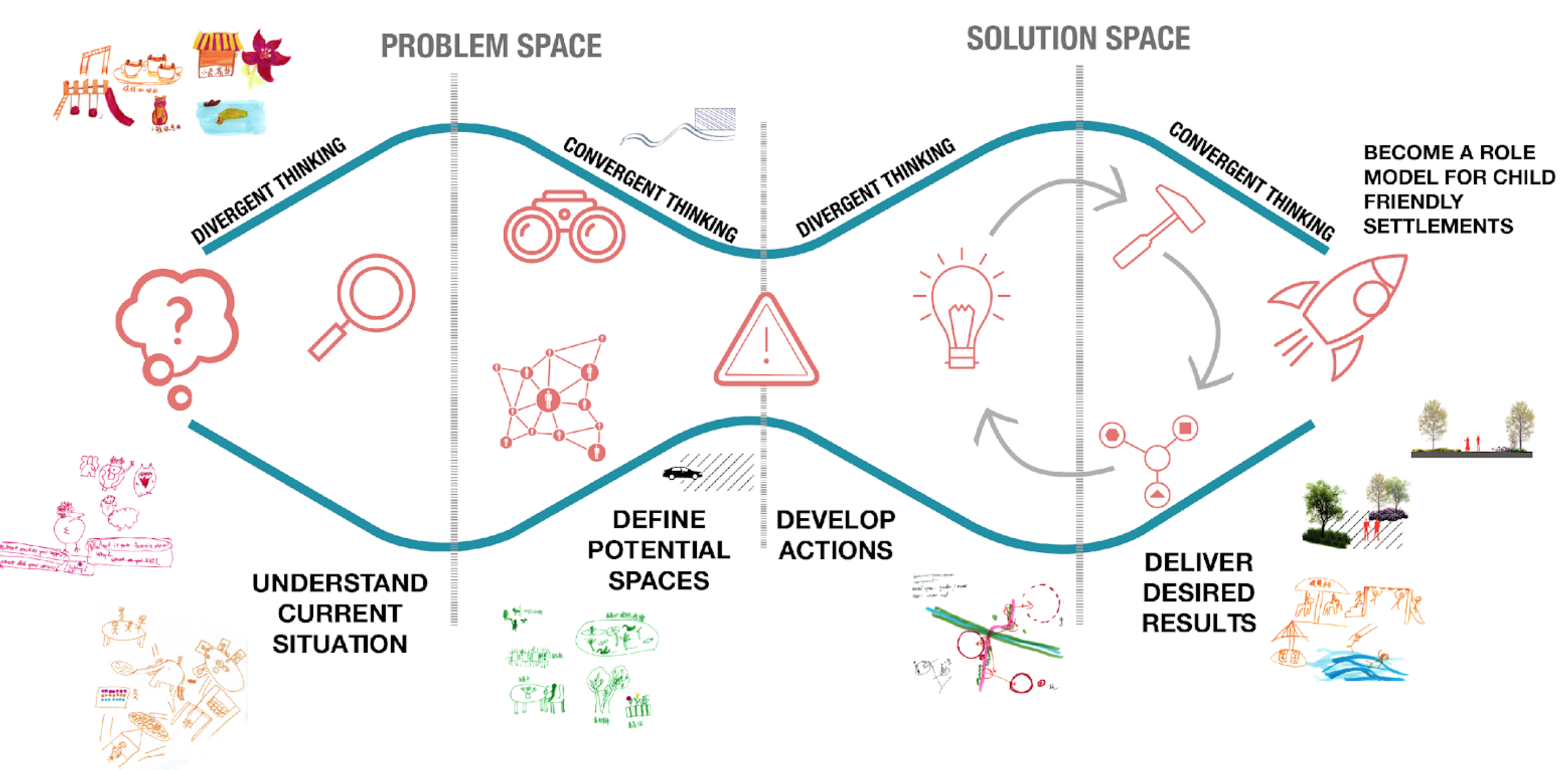

“From a maze to a(maze)d” is a proposal built on a double-diamond framework that allows to keep a documentation of the design process in a flexible level of detail, fostering co-creation and adaptability to the circumstances. Following this method, the project can be explained in four different stages: discover, define, develop and deliver.

Fig. 1 The process of four stages

ZOOMING IN

In the first discovering stage, the team performed an assessment of the neighbourhood, using tools that would allow an understanding of the current situation of the Mindong neighbourhood. The analysis is performed in the spatial and social elements of the place.

Through observation, meetings with the neighbours, and interviews on the streets, the team began to identify user needs and develop initial ideas.

The team specially asked the children about their daily activities and journeys, taking strongly into account their feelings in the different spaces they occupy.

“I spend most of my day doing homework and studying.” “I don’t go outside to play.” “There is no place here to eat or have an ice-cream,” and “the park and plazas are for the elderly.” These were some of the most common responses gathered while speaking with the children.

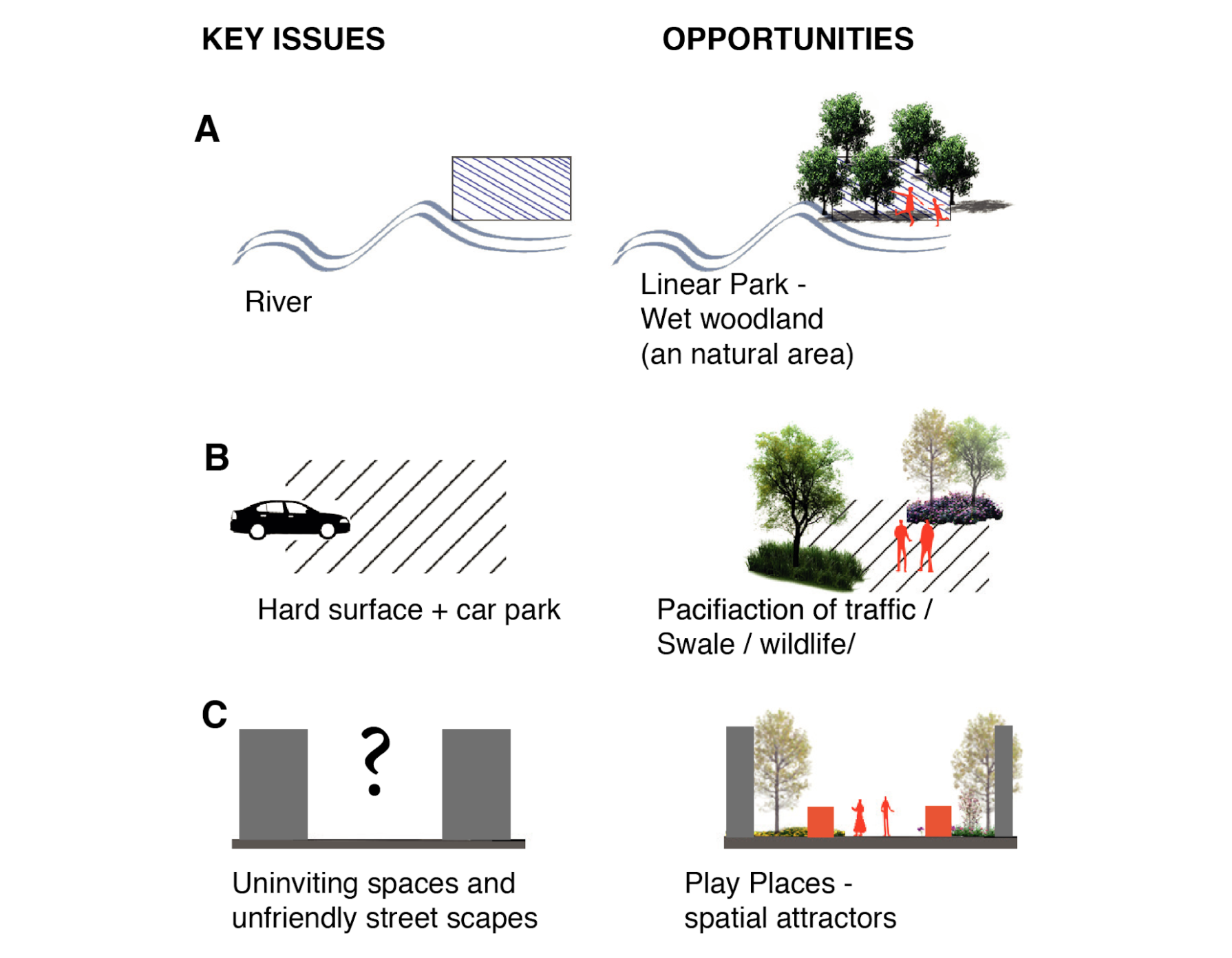

Fig. 2 & Fig. 3 Challenges and Potentials discovered within the observation phase and interviews

By observation, it was also possible to identify that the car is the strongest occupant of the public space, including the sidewalks. A car-oriented design results in poor walkability and hard access for the children to enjoy the public space. There are also very limited places for playful activities or even for studying and meeting. Moreover, the waterfront was not even mentioned by the children, despite its strategic position and potential to serve as a delimited space for recreation and green areas. The waterfront area has a restricted access, due to a fence and the presence of different ground levels.

The discovery process or assessment gave clear insights to the team about the main challenges of the community, as well as its potential to become a child-friendly neighbourhood. Additionally, it gave us a clear idea of how open the community was to start a co-creational process. This is important for the local government and practitioners, as people would like to be heard but also would like to participate and take responsibility and ownership of their neighborhood transformation.

CAPTURING

Moving forward to the second stage in the process, the team proceed to defining the potential spaces, as well as narrowing down the challenges that the community faces.

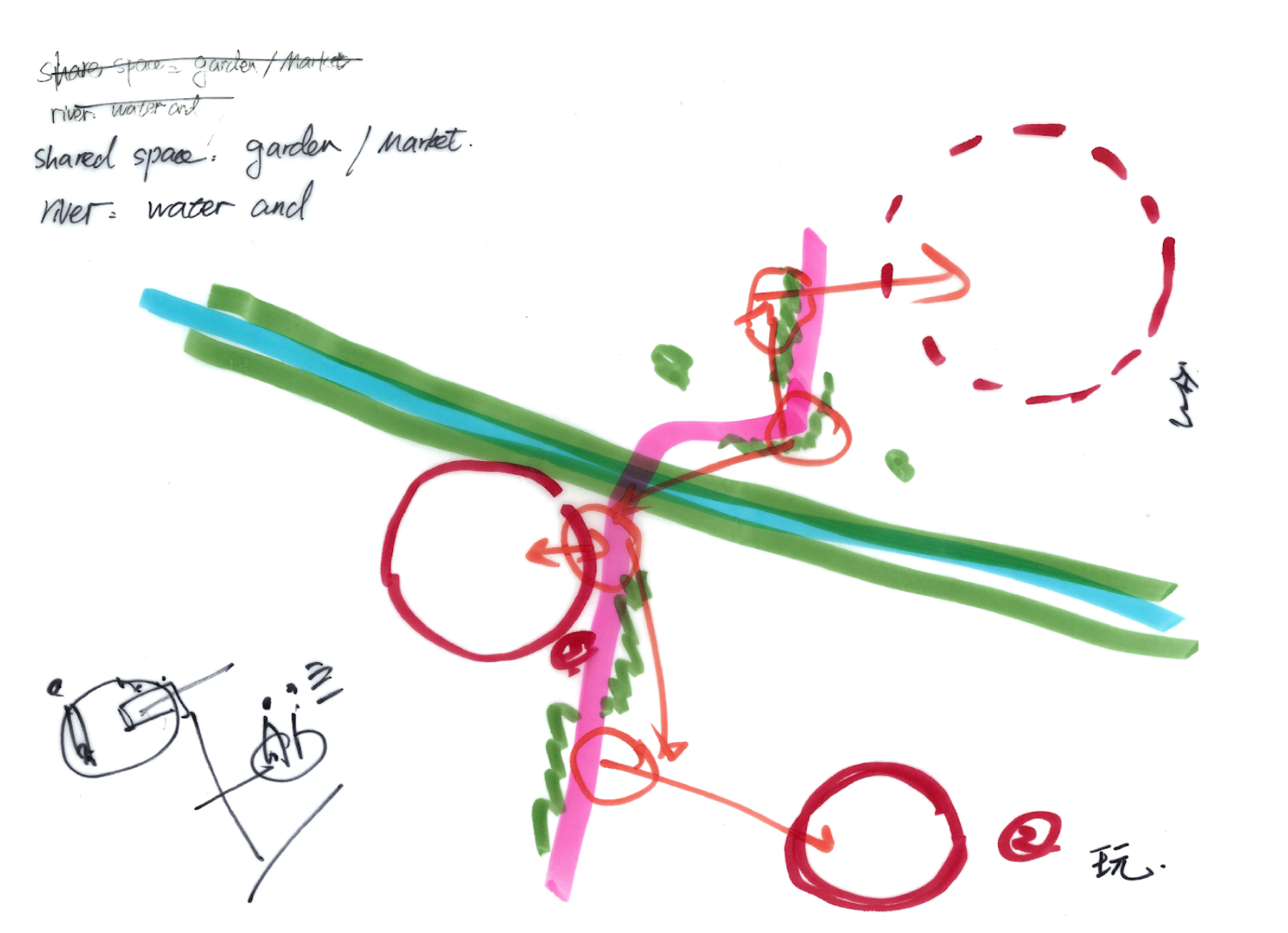

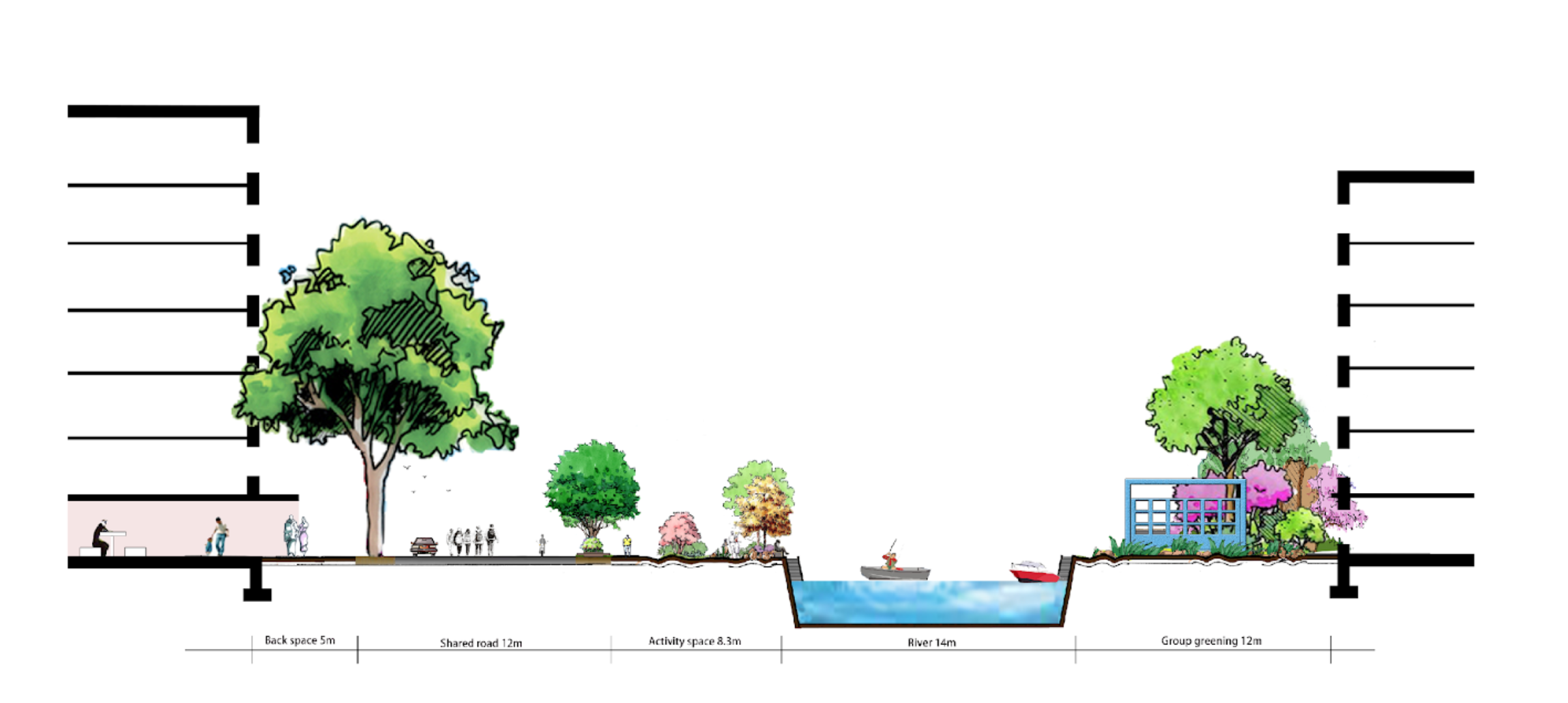

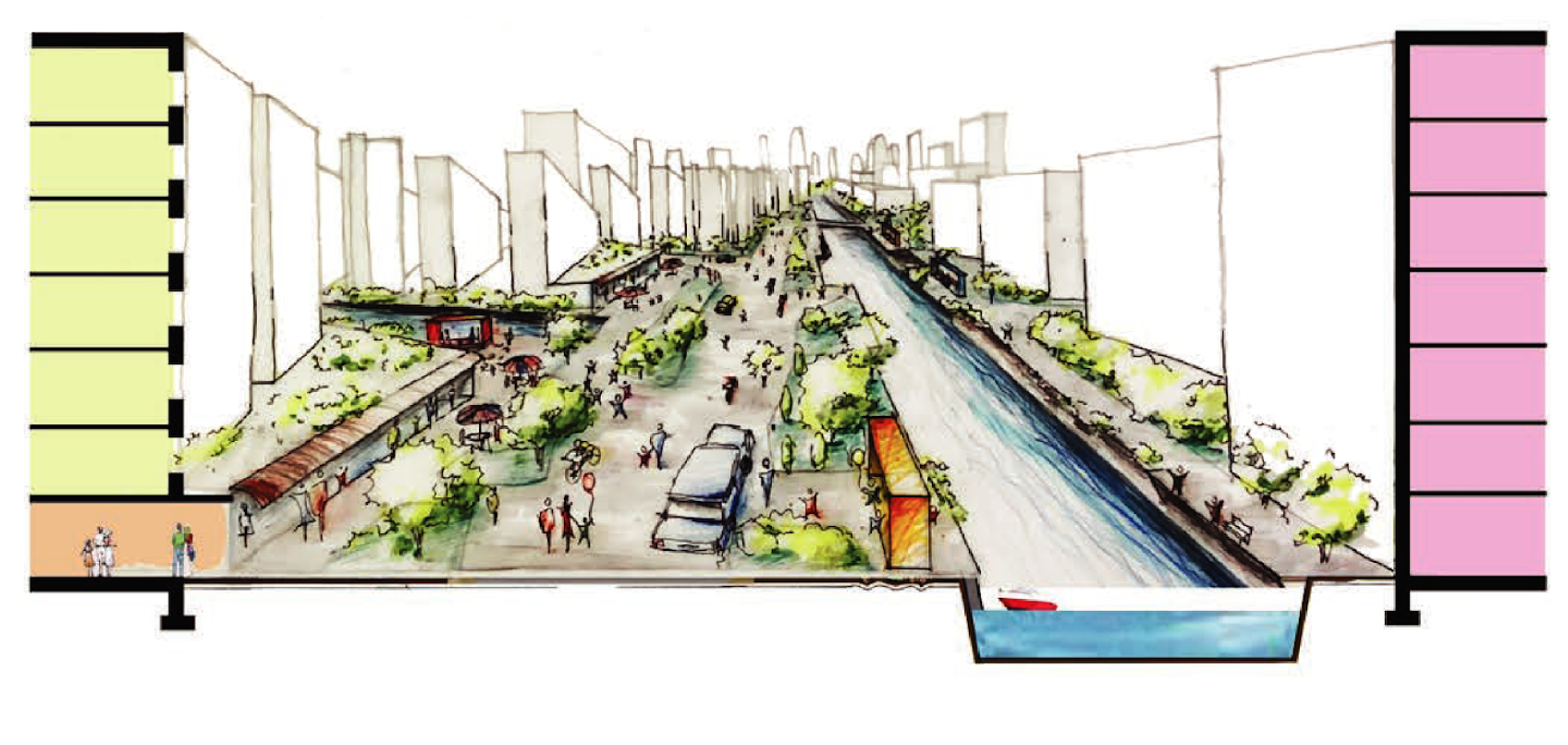

In the defining stage, the river and waterfront are identified as a main element of the area, as well as a significant spot for possible interventions. However, to achieve a child-friendly neighbourhood, it is not sufficient by focusing on one place only. It is necessary to intervene many spots in the area to assure easy, safe and independent mobility for the children, providing sensorial opportunities and a network of spaces that would allow different activities for them and their caretakers.

Taking this into account, three layers of intervention were defined: (1) the waterfront, as a significant central landmark, (2) several empty spots across the neighbourhood which represent spaces for the development of a variety of activities closer to each kid’s house or block, (3) the streets and sidewalks as a whole grid which should be transformed to facilitate non-motorized mobility and interconnection.

Considering the findings for the assessment phase and having the children described their feelings as being “trapped in the neighbourhood”, we got the impression that the neighbourhood landscape could be compared to a maze. A place with a clear border delimitation but still very difficult to find its way inside of it. It is a boring and monotonous place, considering that the buildings and structures of the neighbourhood look very similar and there is a lack of landmarks and sensorial opportunities. However, we can bring magic to the spaces inside the maze and make it a fun and playful place in which children would like to get lost and explore every corner. Therefore, our project is named: From maze to a(maze)d.

In the third developing stage, we propose an action plan for the different layers previously defined: (1) waterfront, (2) spots inside the neighborhood and (3) a network of paths for intermodal mobility.

As the strategic plan illustrated (see Fig.1), the actions respond to three different components: spatial, social and environmental. Each action is developed in the consideration of the UNICEF principles for child-responsive urban planning and mentions the desired results expected for each intervention. Additionally, we have followed the methodologies of the City at Eye Level for Kids, the Mix and Match tool by Eindhoven University and, the Bernard van Leer Foundation ICTN series to propose design solutions, but also give suggestions for programming and policy making. ( Doumpa et al. 2019; Krishnamurthy et al. 2018; UNICEF 2018, BvLFoundation, 2019)

REVEALING

The project was presented to the Mingdong community locals, as well as Ningbo autorithies and the organizers of the YPP workshop, proposing the following:

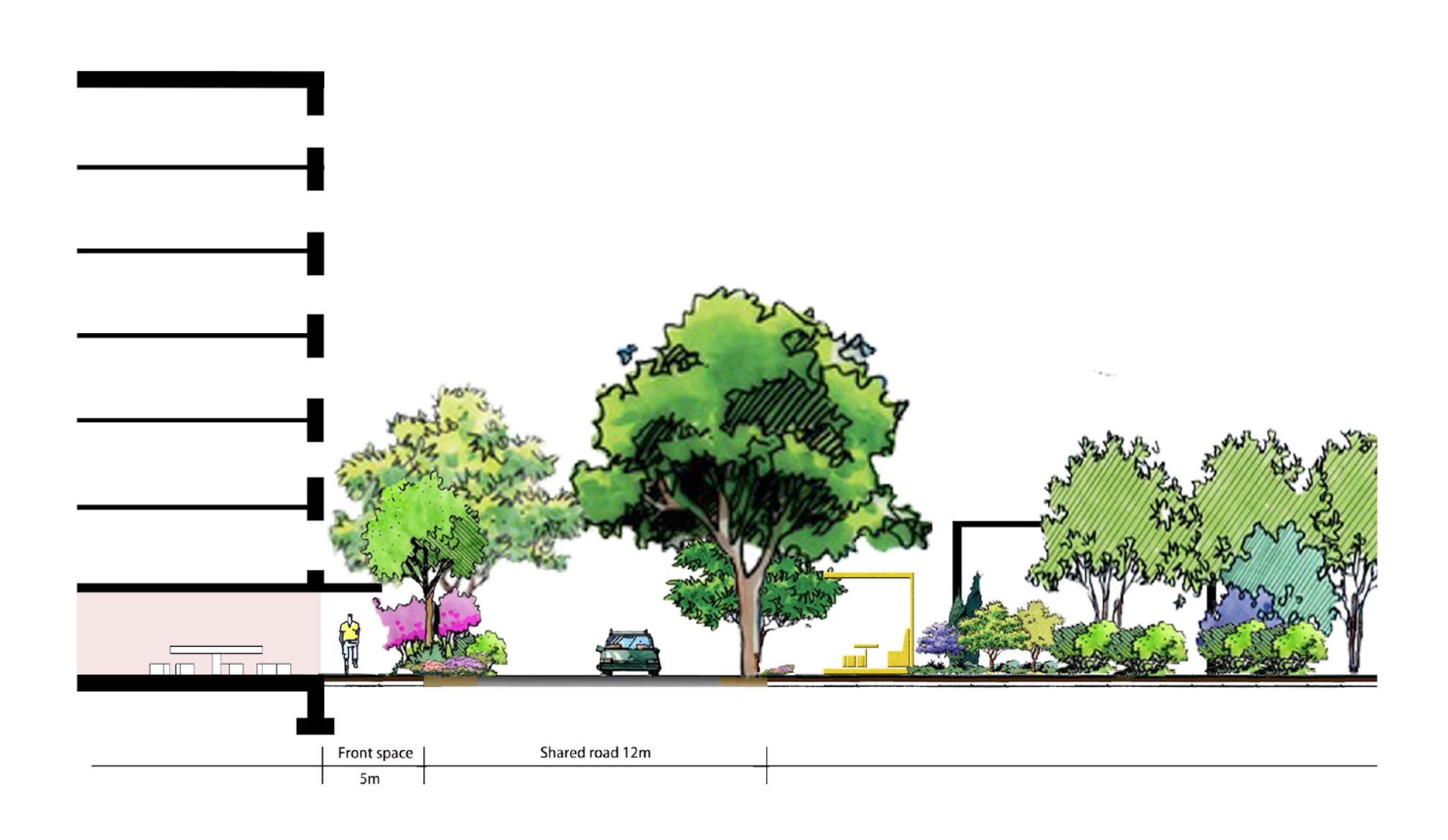

For the waterfront, the main actions are to unify the street level from the river to the plinths. This will facilitate the mobility for all inhabitants. Additionally, we propose the elimination of the fence that restricts the access to the waterfront. In this way we can obtain a mixed-use open space for diverse users. Cars can still pass through the road, but they are only allowed to park on one side. A strategy of traffic pacification is adopted in order to promote pedestrians, bikes and other non-motorized mobility, diminishing the dominant use of cars in the area following a pull and push approach. (Muller et al, 1992; NACTO, 2018)

Considering the social aspect, we believe that the creation of this unique public space will offer a platform, fostering economic opportunities for shop owners in the area. Moreover, the easy access to the waterfront will revive the old and traditional uses of the place. As a desired result, more activities will take place along the riverside. This will bring people together, allow social interactions and promote more face-to-face contacts and activities outdoors. We also propose the addition of vegetation and the maintenance of the green areas, building towards a natural and healthier environment.

ZOOMING OUT

Child-responsive urban planning does not refer to only answering what would be good for children, it should be about what children think would be good for the whole community. Children should be a crucial part of the decision making. They are aware of their needs and the wellbeing of others at the same time and considering their thoughts represents a critical opportunity for urban planners to change things for better. In our experience, children gave the inspiration and insights in order to plan an strategy to transform Mindong in a place where everyone can enjoy, be healthy and life save and happily.

The final aim is that the Mindong neighbourhood will become a national and international pilot case of child-responsive urban planning, following spatial, social and environmental principles. Through focusing on and listening to children, our fundamental objective is to transform Mindong from a maze to place where the Mindong inhabitants will be a(maze)d by the new urban environment that will benefit the whole community.

Credits

This text is an adaptation of the team’s report to ISOCARP. Credits go to the team tutor and all team members: Jing Xie, (Associate Professor at the University of Nottingham, Ningbo-China), Iva Schokoska (EXHIBIT), Yiwen Jin ( Zhejiang Mingyang Design Engineering Co. Ltd.) Chenhong Xia (NBPI), Kejun Shao (Wenzhou University), and Viviana Cordero (Huasipichanga).

References:

Krishnamurthy, S., C. Steenhuis, and D. A. H. Reijnders. 2018. “Mix & Match: Tools to Design Urban Play.” https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:pure.tue.nl:publications%2F9a7d00ad-8368-4579-839e-7e82a4f962aa.

Bernard van Leer Foundation, 2019. An Urban95 Starting Kit. Ideas for action. https://bernardvanleer.org/app/uploads/2019/06/BvLF-StarterKit-Update-Digital-Single-Pages.pdf

Müller, P., Schleicher-Jester, F., Schmidt, M.-P. & Topp, H.H. (1992): Konzepte flächenhafter Verkehrsberuhigung in 16 Städten”, Grüne Reihe des Fachgebiets Verkehrswesen der Universität Kaiserslautern No. 24.

NACTO, Global Street Design Guide, 2018